School District Gets Expensive Lesson on Prompt Payment Law. But Did the Court Get it Right?

My kids don’t like riding in my car.

I urge them to look outside the window (I don’t have DVD), suggest that they roll down their windows to get some fresh air (rather than have me turn on the A/C) and persist on listening to that archaic device called the radio (I don’t “stream”).

Plus, I make them play “Dad Games.” Like Synonyms.

In Synonyms, I say a word, and the next person has to come up with a synonym for that word until someone can’t think of another synonym. Sometimes, I take a walk on the wild side, and play “Antonyms.”

Things can get heated, though. Like when someone says a word and there is a disagreement over whether that word is a synonym or not.

The next case, FTR International, Inc. v. Rio School District, California Court of Appeal for the Second District, Case No. B238618 (January 27, 2015), also involved a disagreement over synonyms . . . except that the loser had to cough up nearly $10 million.

California’s Prompt Payment Laws

California has a number of prompt payment laws applicable to construction projects.

The prompt payment laws have as their goal the “prompt payment” of project funds by owners to direct contractors, direct contractors to subcontractors, and subcontractors to lower-tiered subcontractors and provide for hefty penalties – 2% per month, or 24% per annum, which exceeds the interest rates on most credit cards) – if payments are not made within mandated time frames.

What makes the prompt payment laws confusing, however, is that they are scattered throughout the state’s Business and Professions Code, Public Contracts Code and Civil Code; their applicability depends on the type of project, the type of payment, and who is paying; and, as the FTR International case highlights, the terminology used in each statute is slightly different.

The FTR International Case

In 1999, general contractor FTR International, Inc. (“FTR”) entered into a $7.3 million construction contract with the Rio School District (“District”) for the construction of the Rio del Norte Elementary School in Oxnard, California.

During construction, FTR submitted approximately 150 proposed change orders (“PCO”). Most of the PCOs were denied by the District on the grounds that they were for work already covered by the contract, the amounts claimed were excessive, or that the PCO was not timely filed.

Construction of the project was completed in 2001.

Pursuant to the parties’ contract, the District withheld retention of 10%. At the time of completion, the District held $676,436.49 in retention. However, that amount was subject to various stop payment notices served by FTR’s subcontractors, the last of which, was released in 2004.

Nevertheless, even after the last stop payment notice was released, the District refused to release the retention to FTR.

FTR later sued the District for breach of contract, prompt payment penalties under Public Contract Code section 7107, attorney’s fees, interests and costs. After a 243-day court trial, the trial court found in favor of FTR and awarded it a whopping $9,356,124.81, more than the original contract itself.

Of the $9 million award, prompt payment penalties of $1,537,404.96, on top of the $676,436.49 in retention withheld by the District, was awarded to FTR at the statutory penalty rate of 2% per month from the date the last of the stop payment notices were released in 2004.

The District appealed.

The Court of Appeal Opinion

On appeal, the District argued that prompt payment penalties should not have been awarded because there was a “good faith dispute” between the District and FTR and, that under Public Contract Code section 7107(c), “[i]n the event of a dispute” a public entity is entitled to withhold up to 150% of any disputed amount from final payment:

Within 60 days after the date of completion of the work of improvement, the retention withheld by the public entity shall be released. In the event of a dispute between the public entity and the original contractor, the public entity may withhold from the final payment an amount not to exceed 150 percent of the disputed amount. . . .

Public Contract Code §7107(c).

The Court of Appeal, however, disagreed. “The purpose of [ ] retention is to provide security against potential mechanics liens and to insure [sic] the contractor will complete the work properly and repair defects,” stated the Court, but because the stop payment notices had been released there was “nothing for which security was required.”

The Court also rejected the District’s reliance on an earlier case, Martin Brothers Construction, Inc. v. Thompson Pacific Construction, Inc., 179 Cal.App.4th 1401 (2009), in which the Court of Appeal for the Third District had held that a subcontractor was not entitled to recover prompt payment penalties from a general contractor because there was a good faith dispute. Stating that it would “[d]ecline to follow Martin Brothers,” the Court stated:

The purpose of section 7107 is to deter public entities from improperly withholding retention payments. . . . Section 7107’s purpose of ensuring the prompt release of retention funds would not be served if any dispute justified retaining the funds. There is no reason to allow a public entity to retain the funds once their purpose of providing security against mechanics liens [Note: while the Court mentions “mechanics liens,” a mechanics lien is not an available remedy on public works projects in California] and deficiencies in the contractor’s performance has been served. Unless the dispute relates to one of those purposes, the public entity will not be protected from the statutory penalty. FTR’s action against District is not such a dispute.

And, finally, the Court rejected the District’s argument that recent amendments to the prompt payment statutes demonstrated that Martin Brothers was properly decided. In support of its argument, the District noted that Civil Code section 3260 (which was later rectified at Civil Code section 8812) originally provided: “In the event of a dispute between the owner and the original contractor, the owner may withhold from the final payment an amount not to exceed 150 percent of the disputed amount.”

However, as recodified, argued the District, Civil Code section 8812 now provides: “If there is a good faith dispute between the owner and direct contractor as to a retention payment due, the owner may withhold from final payment an amount not in excess of 150 percent of the disputed amount.”

While the California State Legislature specifically referenced “retention” in Civil Code Section 8812 but did not include any similar reference to “retention” in Civil Code Section 7102, concluded the District, it showed that Martin Brothers was correctly decided because Section 7107 permits a public entity to withhold up to 150% of any disputed amount from final payment, whether related to retention or not.

The Court, however, disagreed. Pointing to the legislative history of Civil Code section 8812, the Court pointed out that the recodification of Civil Code section 3260 to Civil Code section 8812 was “intended to be nonsubstantive.” The Court also mentioned as “noteworthy” that the state legislature added the term “good faith” to Civil Code section 8812 but not to Public Contract Code section 7102, but despite the lack of such amendment to Section 7102, “[n]o one would seriously argue section 7101 . . . allows a public entity to create a dispute in bad faith.”

But Did the Court Get it Right?

I’m not so sure.

As I mentioned, California’s prompt payment laws are scattered throughout the state’s Business and Professions Code, Public Contracts Code and Civil Code; their applicability depends on the type of project, the type of payment, and who is paying; and the terminology used in each statute is slightly different.

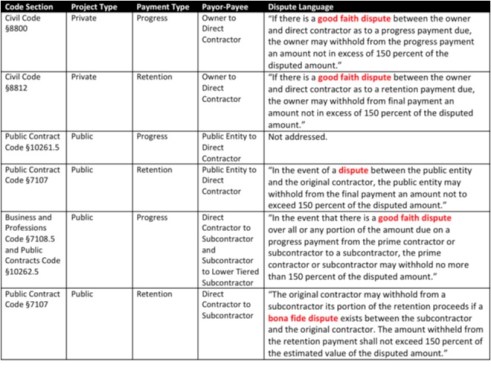

Here’s a table summarizing some, but not all, of California’s prompt payment laws:

There are a few things worth noting from this table:

There are a few things worth noting from this table:

- Differences between private and public owners: Private owners are allowed to withhold both progress and retention payments but only if there is a “good faith dispute.” Public owners, on the other hand, are allowed to withhold retention if there is simply a “dispute.”

- Differences between public owners and public works contractors: Once again, Public owners are allowed to withhold retention if there is simply a “dispute.” However, public works contractors are only allowed to withhold progress and retention payments if there is a “good faith dispute” or “bona fide dispute.”

- Difference between progress and retention payments for public works contractors: For progress payments, a public works contractor may withhold if there is a “good faith dispute.” However, for retention, a public works contractor may withhold if there is a “bona fide dispute.”

Words, of course, have meaning. However, “dispute,” “good faith dispute,” or “bona fide dispute” are not defined under the prompt payment statutes. And this, of course, raises questions like:

- Is a “good faith dispute” more limited than just a “dispute,” or are they synonymous?

- What is the difference, if any, between a “good faith dispute” and a “bona fide dispute,” or are they synonymous?

- Why is it that private owners and public works contractors may only withhold if there is a “good faith dispute” or “bona fide dispute” but a public owner can withhold if there is simply a “dispute,” or are the terms synonymous and there is no difference?

Now, I recognize when I say, “only if there is a ‘good faith dispute’ or ‘bona fide dispute'” and “simply a ‘dispute,'” that I’m using loaded words – because it suggests that a “good faith dispute” or “bona fide dispute” provides more limited withholding rights than just a “dispute” – but wasn’t that the very issue in FTR International?

According to the opinion, the District contended that it withheld the retention because there was a “good faith dispute.” However, under Public Contract Code section 7107(c), the District could withhold retention if there was simply a “dispute” not only if there was a “good faith dispute.”

Likewise, while the Court of Appeal says that it would “decline to follow Martin Brothers,” I wonder if Martin Brothers is really relevant to begin with, since Martin Brothers involved a general contractor on a public works project who withheld retention from a subcontractor under a prompt payment statute which permits a general contractor to withhold retention if there is a “bona fide dispute.”

So, not only are we potentially mixing apples (i.e., “good faith disputes“), and oranges (i.e., “bona fide disputes“), with bananas (i.e., “disputes“), we’re potentially mixing fruits (i.e., prompt payment laws applicable to public works contractors) with meat from the deli department (i.e., prompt payment laws applicable to public owners).

I think the opinion comes closest to the issue when the Court says:

It is noteworthy the Legislature also added the requirement that the dispute be in “good faith” to Civil Code section 8812, subdivision (c). The Legislature did not amend section 7107, subdivision (c) to add the term “good faith.” No one would seriously argue section 7107, subdivision (c) allows a public entity to create a dispute in bad faith.

I don’t disagree that the state legislature would not have intended to allow public entities to withhold retention in “bad faith.” But what does “bad faith,” or “good faith” for that matter, have to do with public entities when Public Contracts Code section 7107(c) allows a public entity to withhold retention simply “in the event of a dispute” -which, arguably, allows a public entity to withhold retention irrespective of the basis of what that dispute might be – whether it’s a dispute concerning offsets to retention or other dispute concerning the project in general.

For example, while the Court of Appeal states that “[t]here is no reason to allow a public entity to retain funds once their purpose of providing security against mechanics liens and deficiencies in the contractor’s performance has been served,” I can see where a public entity might want to withhold retention outside of protection from stop payment notices [Note: as mentioned above, a mechanics liens is not an available remedy on public works projects in California] or detective or incomplete work such as to offset for liquidated damages, to compensate a public entity for consequential damages, etc.

Now, this is not to say that I disagree with the outcome of the case, since there was no indication that the District suffered any damage at all as opposed to just holding onto the retention on the ground that FTR’s PCO claims were invalid. I do, however, question the Court’s rationale in reaching the outcome it reached.

2 Responses to “School District Gets Expensive Lesson on Prompt Payment Law. But Did the Court Get it Right?”

[…] past year we wrote about a case involving California’s prompt payment laws and the current state of confusion […]

Prompt payment penalties are a godsend for the general contractors, especially those who work on government contracts, since some government officials become so highhanded, uncaring or simply lazy that they think, they can get away with any thing. Kudos to the court’s decision!